Tags

AI, ethics, leadership, life, philosophy, politics, problem finding, problem formulation, problem framing, problem solving, thinking, truth

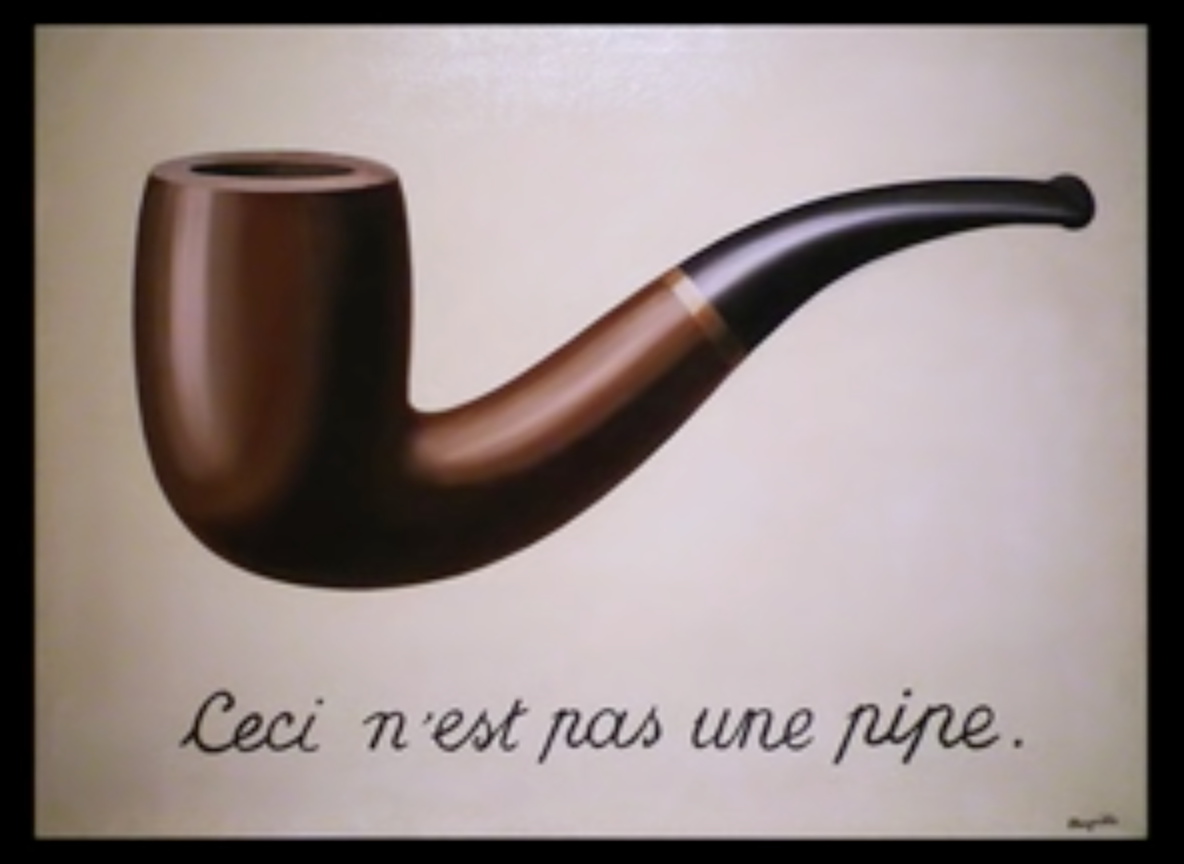

Reframing the Problem: Paperwork & Working Paper

This is the second in a series about the importance of correctly framing a problem. Generally, at least in formal American education, the teacher gives you a problem. Not only that, if you are in Algebra class, you know the answer will be an answer based in Algebra. If you are in art class, you’re expected to paint a picture. If you painted a picture in Algebra class, or wrote down a formula in Art Class, they would send you to the principal for punishment. But in real life, how a problem is presented may actually be far from the most elegant solution to the real problem.

Doing a google search on “problem solving” just now yielded 208 million results. Entering “problem framing” only had 182 thousand. A thousand times as much emphasis on problem solving as there was on problem framing. [Update: I redid the search today, a little over three years later. On 3/6/2024, I got 542M hits on “problem solving” and 218K hits on “problem framing” — increases in both but the ratio is even worse than it was in 2021] [Second update: I did the search today, Dec. 4th, 2025, and the information was not given–but that’s the subject of a different post].

Let’s think about that ratio of 542 million to 218 thousand for a moment. Roughly, that’s 2000 to 1. If you have wrongly framed the problem, you not only will not have solved the real problem; what’s worse, you will have often convinced yourself and others that you have solved the problem. This will make it much more difficult to recognize and solve the real problem even for a solitary thinker. And to make a political change required to redirect hundreds or thousands will be incalculably more difficult.

All of that brings us to today’s story. For about a decade, I worked as executive director of an AI lab for a company in the computers & communication industry. At one point, in the late 1980’s, all employees were all supposed to sign some new paperwork. An office manager called from a building several miles away asking me to have my admin work with his admin to sign up a schedule for all 45 people in my AI lab to go over to his office and sign this paperwork as soon as possible. That would be a mildly interesting logistics problem, and I might even be tempted to step in and help solve it. More likely, if I tried to solve it, some much brighter & more competent colleague would have done it much faster.

But why?

Why would I ask each of 45 people to interrupt their work; walk to their cars; drive in traffic; park in a new location; find this guy’s office; walk up there; sign some paper; walk out; find their car; drive back; park again; walk back to their office and try to remember where the heck they were? Instead, I told him that wasn’t happening but he’d be welcome to come over here and have people sign the paperwork.

You could make an argument that that was 4500% improvement in productivity, but I think that understates the case. The administrator’s work, at least in this regard, was to get this paperwork signed. He didn’t need to do mental calculations to tie these signings together. On the other hand, a lot of the work that the AI folks did was hard mental work. That means that interrupting them would be much more destructive than it would to interrupt the administrator in his watching someone sign their name. Even that understates the case because many of the people in AI worked collaboratively and (perhaps you remember those days) people were working face to face. Software tools to coordinate work were not as sophisticated as they are now. Often, having one team member disappear for a half hour would not only impact their own work, it would impact the work of everyone on the team.

Quantitatively comparing apples and oranges is always tricky. Of course, I am also biased because my colleagues are people I greatly admire. Nonetheless, it seems obvious that the way the problem was presented was a non-optimal “framing.” It may or may not have been presented that way because of a purely selfish standpoint; that is, wanting to do what’s most convenient for oneself rather than what’s best for the company as a whole. I suspect that it was more likely just the first idea that occurred to him. But in your own life, beware. Sometimes, you will mis-frame a problem because of “natural causes.” But sometimes, people may intentionally hand you a bad framing because they view it as being in their interest to lead you to solve the wrong problem.

Politics, of course, takes us into another realm entirely. People with political power may pretend to solve one problem while they are really following a completely different agenda. One could imagine, for instance, a head of state claiming to pursue a war for his people when he’s really doing it to keep in power. Or, they could claim they are making cities safe by deploying troops when they are really interested in suppressing the vote in areas that can see through his cons. Or, a would-be dictator could claim they are spending your tax dollars to make government more efficient when that has nothing to do with what they are *actually* doing–which is to collect data on citizens and make the government ineffective in order to have people lose confidence in government and instead invest in private solutions.

Even when people’s motivations are noble or at least clear, it is still quite easy to frame a problem wrongly because of surface features. It may look like a problem that requires calculus, but it is a problem that actually requires psychology or it may look like a problem that requires public relations expertise but what is actually required is ethical leadership.

——————————————————

Author Page on Amazon

Tools of Thought

A Pattern Language for Collaboration and Cooperation

The Myths of the Veritas: The First Ring of Empathy

Essays on America: The Stopping Rule

Essays on America: The Update Problem