Not-Separateness

It seems odd to specify a property of natural order in terms of what it is not. On the other hand, I cannot come up with a positive alternative that doesn’t bring other connotations with it. I think it’s related to “unified” or “integral” or “belonging” or “inter-related” but none of those seem quite so on the mark as does “Not-Separateness.”

Christopher Alexander’s degree from MIT was in architecture. Part of the reason he may have chosen this particular term is in reaction to some examples of architecture in which the architect seems to be in the business of constructing a building whose primary purpose is to make them famous regardless of what that building does to the neighborhood or the occupants.

Imagine Mr. Bigg designs a house that is a perfect black cube set on on vertex. In effect, this design says to me: “I am BIG. I am Mr. Bigg! I am a genius! You would have never been brilliant enough to design a house that is a cube on its vertex! You would have wasted your time and done something mundane like placed the cube on the ground on one of its faces. Anyone could think of that! But I put it on a vertex!” Indeed, we may easily imagine that he says words to this effect when his interview is reported on in the (mythical) architectural journal, Things that look different!

“Mr. Bigg, you made the Bigg House out of black steel and black glass. Some critics have argued that this doesn’t fit with the existing neighborhood of stone cottages with thatched roofs.”

“Of course, little minds will always criticize Bigg ideas.”

“Yes, yes. It also means that the construction costs of the house were quite high. And, the estimated costs of heating and cooling are much higher as well.”

“Nothing that a worthwhile (i.e., wealthy) client can’t afford.”

“Some have also argued that it is inconvenient for the occupants who have to walk up and down at a steep angle and that furniture such as dressers, tables, chairs, and beds do not accommodate well to the tilted walls.”

“Let me ask you aquestion. Would you have ever thought of putting a cube on its corner? No. I didn’t think so!”

Of course, this is exaggeration. But not much.

We would hope that User Experience designers take into account the users, their tasks, their contexts, and the way in which their designs interact with other related artifacts, people and processes. We would hope that applications and artifacts and services are all designed with the property of “Not-Separateness.”

In the early 1980’s, I worked in the IBM Office of the Chief Scientist. My main assignment was to get IBM to pay more attention to the usability of its products. As part of that process, I visited quite a few IBM development labs around the world and spoke to many development teams. On many of these visits, I was accompanied by the Chief Scientist, a brilliant physicist, who “got” usability.

On one occasion, we watched a new printing technology. Instead of printing out black printing on a white sheet of paper sized 8.5” x 11” or A4, this printout was of no standard size. The printing was black on a shiny silver sheet that curled severely. The Chief Scientist asked the head of the development team how they envisioned this being used.

Chief Scientist: “Once someone printed this out, what would they do with it?”

Answer: “Oh, anything they liked.”

Chief Scientist: “I mean, would people tape this into a notebook or paste it? Or would you imagine notebooks that would bind such paper?”

Answer: “It’s not up to me to decide how people would use it. Doesn’t it look cool?”

Another type of answer we heard more than once to the question, “How would this be used?”

— “Oh, it’s a (replacement/upgrade) for this other IBM product.”

“But who would use it and for what?”

“It has three main components. Would you like a description of the components?”

Of course, there is a place for “playing around” with technology and thereby discovering things which someone else may find a use for. But in design and development of a product or service, having a clear notion of context of use and the users and tasks is fundamental. Of course, other users may appropriate a product or service for purposes beyond those envisioned by the original designers. That’s cool.

What’s not cool is designing a device that is to be used in the bright outdoor sunlight and then testing the display in a typical office environment. Have you ever run across something like that? I have.

A more subtle lack of contextualization in design occurs when the design team fails to realize how many interruptions happen to the user while they are trying to accomplish a single task with the new application. If you “test” the application while the user is in a quiet “usability lab” and can give your tasks their undivided attention, then necessitating them to remember the invisible internal state of “Insert” versus “Edit” mode may not be a big deal at all. They will simply remember. But in their office environment, they may be interrupted by a phone call, a message, or their boss entering their office and asking a series of detailed questions. If they now go back to the task at hand, there is about a 50-50 chance that they will correctly guess whether they are in “Edit” mode or “Insert” mode.

A design which shows the property of Not-Separateness is the natural result of a process which shows not-separateness. Here are a few common ways to help ensure the design process grows organically from the users and their goals & contexts.

* Put people on the design team who are familiar with the users, and/or their tasks, and/or their contexts.

* People on the design team observe people engaging in the relevant processes, whenever possible, not — or not only — in a “Usability Lab” but in the actual work environment.

- Jointly develop a product or service with the group who will use the product or service.

- Observe people actually using product P (or service S), version N so that version N+1 will be better attuned to the needs of the users.

- Gather and understand feedback from service calls and help desks and customer complaints in order to improve over time.

There will be benefits to a company who takes such approaches beyond initial sales. If you’ve done any gardening, you will appreciate that the quality of the tomatoes you enjoy eating is related to the quality of the soil and the quality of the care you give the tomatoes. Similarly, a product or service that has the quality of Not-Separateness will not only be useful — users will fight to keep your product or service. It becomes integrated with the environment. To change the brand means that they will have to change the way they work; possibly even with whom they work. Not-Separateness is likely a path to what business people like to call a “Cash Cow.”

If you’ve ever walked through a neighborhood after a hurricane, you’ve likely seen many uprooted trees. When you look at the roots of an uprooted tree, what do you see? Of course, you see roots. But what else? You see rocks and soil all around and embedded into the roots. They are Not-Separate. In a hurricane, there are typically not only high winds. There is also a lot of rain. The trees are hit with a double whammy. The wind pushes the tree but the rain weakens the solid soil in which the tree is embedded. It is the combination that makes it very difficult for the tree to “hold on” and keep from falling over.

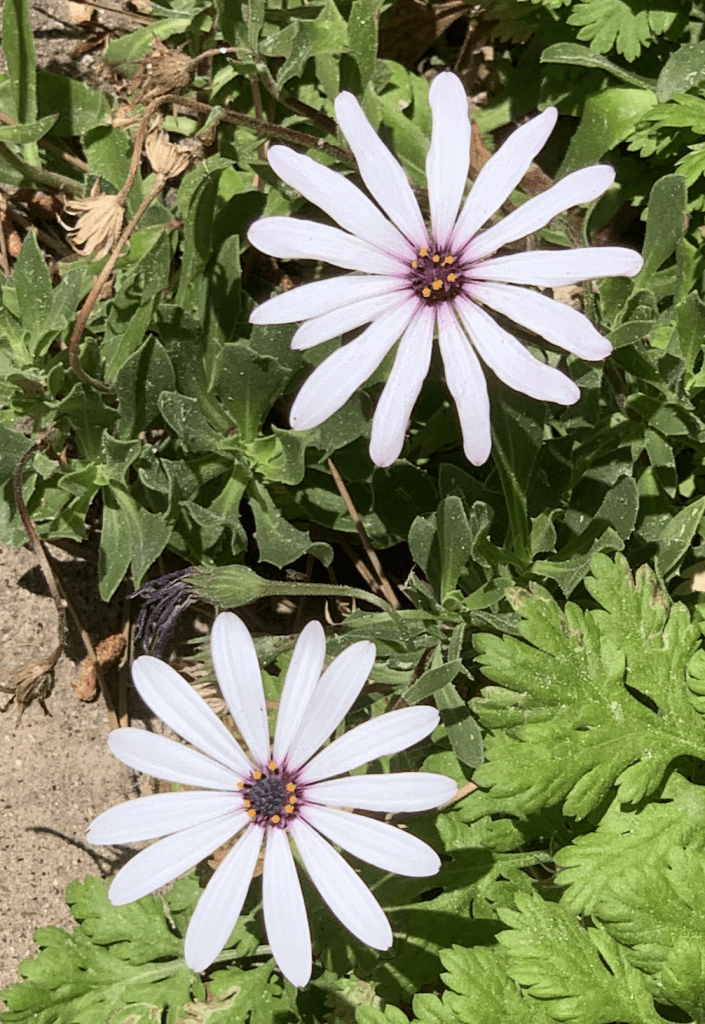

Living things, just like us, have a 4.5 billion year history of living. The living things adapt over time to their environment and they mold the environment to their needs. They are not separate. Flowers appeal to the insects who pollinate them. The insects who pollinate them are adapted to the characteristics of the flower. A horse adapts to their rider and the rider adapts to their horse. A product or service must have a design that serves the needs of its stakeholders. For a product or service to have maximum beauty, utility, and longevity, it must also have a way to adapt to the changing needs of the users and other stakeholders. At the same time, if the users and their organizations adapt to the product or service, then true Not-Separateness is achieved.

If you want to skimp on designing your product or service, you can make it more separate, more divorced from its context, its users, and its tasks. Of course, if you do that, you also make much easier for your users to abandon your product and switch to a new one.

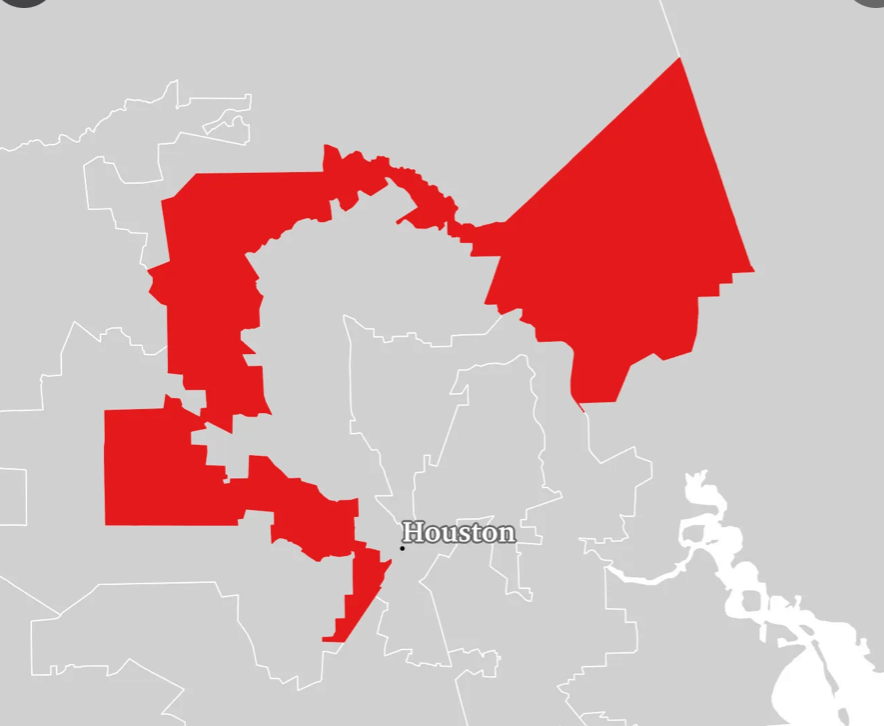

Another way to think about this in terms of systems theory is where you draw the boundary. If you draw a sharp boundary around your product, you may find that, over time, your product becomes ever more peripheral to the community you’re trying to support and your product is ever more fungible with others in its class. On the other hand, if you draw the boundary around the product or service and the people and organizations who provide the product or service then, you are on the path of ever tighter interconnect.

Not-Separateness is not only a quality of good design in terms of not overly separating the context and users from the product or service. It is also a good quality for the organization that produces products & services. Of course, some people today must manage a giant amorphous “organization” of tens of thousands of people so they set up divisions, and departments, and groups, and teams, and positions etc. There may indeed be a “UX Department” and a “Software Department” and a “Hardware Department.” That’s all fine. But it is counter-productive if the UX Department sees itself as separate from the rest of the company. To a great extent the success of the UX Department depends on the success of the Hardware and Software Departments. The Sales Department’s success will, of course, depend partly on the skills of the Sales Department. But it will also depend on the success of the UX Department, HW, SW and Services.

Have you ever had a paper cut? It isn’t just the skin on a quarter inch of the inside of your ring finger that’s cut. You’re cut! It isn’t just that the finger feels pain. You feel pain! That causes you to take steps to ameliorate the pain and to try to make sure it doesn’t happen again. That’s why empathy in leadership is important. A leader must feel empathy for all, or the organization will disintegrate from lack of Not-Separateness. At some point, a raccoon may chew off its own arm in order to escape a trap.

But it isn’t the first thing that occurs to them every time they experience a thorn in the paw!

The raccoon doesn’t say to itself: — “that paw is giving me pain! I’m going to chew it off! Then, it won’t hurt any more.”

Evolution did not evolve a raccoon that acts that way. Self-mutilation exists but it is typically a last resort.

But not for corporations. It is the first thing they think of:

“Our (you name it) Department is not performing well. Let’s lay them off and outsource it.”

What does that say to every thinking employee in the entire corporation? It says:

“You know what? All this talk about teamwork and pulling together is a total bunch of bull$hit. You cannot trust management to do what’s best for everyone. You can only trust them to do what’s best for them.”

Living forms in nature are living forms. Their parts have severe Not-Separateness with the other parts of that form. Often, as in well-functioning families or teams, that extends to all members of the group.

Not-Separateness is essentially deep cooperation. I give to the larger community by becoming a part of it and doing my part in it. I lend strength to the community. In return, I gain strength from that community. It is not a zero sum game, of course. The community, if it is functional, is much stronger than the sum of the individuals in that community.

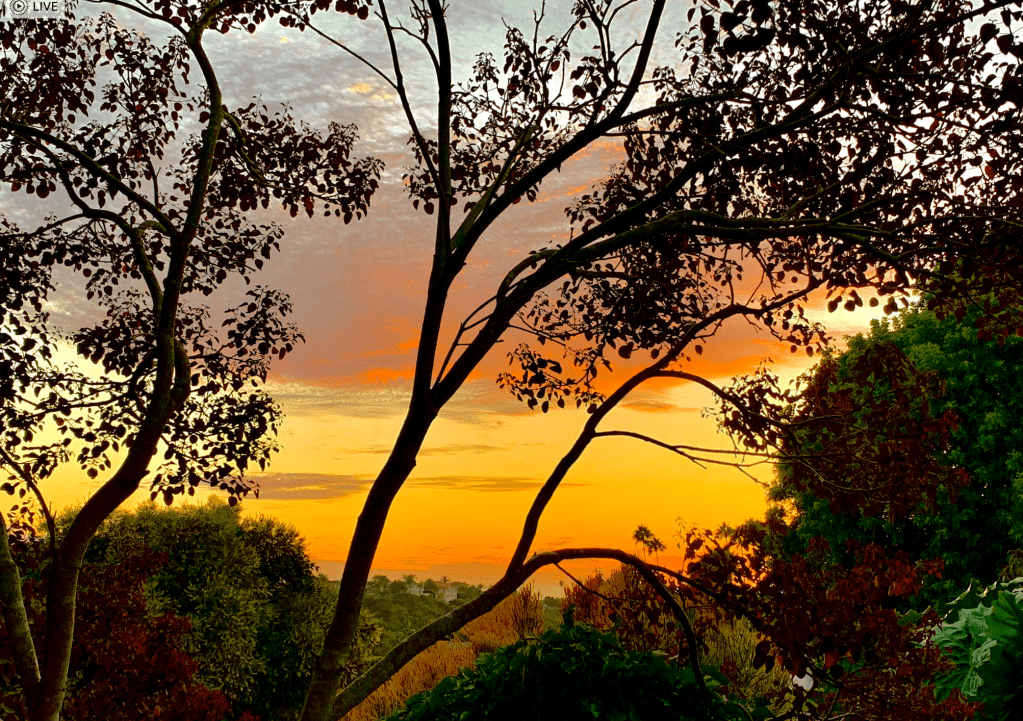

This is so deeply embedded in 4.5 billion years of evolution that it does not surprise me that we recognize beauty as being even more beautiful if it is not separate. Not-Separate enhances beauty because, like all the other properties, it is essential to life.

Eventually, if humanity is to survive, we will realize that Not-Separateness applies to all of us. We are not there yet. But that doesn’t mean we cannot appreciate and design Not Separateness in our products, in our services, and our lives.

—————-

The Declaration of Interdependence

How the Nightingale Learned to Sing

Thomas, J.C. and Kellogg, W.A. (1989). Minimizing ecological gaps in interface design, IEEE Software, January 1989.

Thomas, J. C. (2012). Patterns for emergent global intelligence. In Creativity and Rationale: Enhancing Human Experience By Design J. Carroll (Ed.), New York: Springer.

Thomas, J. C. (2001). An HCI Agenda for the Next Millennium: Emergent Global Intelligence. In R. Earnshaw, R. Guedj, A. van Dam, and J. Vince (Eds.), Frontiers of human-centered computing, online communities, and virtual environments. London: Springer-Verlag.

Thomas, J.C. (1985). Human factors in IBM. IBM Research Report. RC-11267. Yorktown Heights, NY: IBM Corporation.