Tags

cancer, disease, HCI, human factors, innovation, politics, testing, UX, war

Metaphors We Live and Die By: Part 2

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

Today, I want to delve further into the topic of metaphors that we often unconsciously adopt. In particular, I want to look at a common metaphor in four areas: disease, business, politics, and and the role of UX in the entire cycle of product development.

Although I am fascinated by other cultures, my experience is overwhelmingly USA-centric. I am aware that all of the four areas I touch on may be quite different in other countries and cultures. If readers have examples of how different metaphors are used in their culture, I would love to hear about it.

Disease is an Enemy to be Destroyed.

In most cases, American doctors view disease as an enemy to be destroyed. In fact, this metaphor is so pervasive that American readers are likely puzzled that I used the verb “view” rather than “is” in the previous sentence. In American culture, there is also a strong thread of another metaphor about disease: “Disease is a punishment.” This latter metaphor is behind such statements as, “Oh, they had a heart attack! Oh, my! Were they overweight? Did they smoke?” Perhaps I will consider this more fully another time, but for now, I want to examine the view that disease is an enemy to be destroyed.

It seems as though it is an apt metaphor. After all, aren’t many diseases caused by other organisms invading our bodies and doing harm? There are many examples: bacteria (Lyme Disease, pneumonia, ulcers, TB, syphilis), viruses (herpes, Chicken Pox, flu, common cold), protozoa (malaria, toxoplasmosis) or even larger organisms (trichinosis, tapeworms, hookworm).

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

When it comes to considering causality, our thoughts usually travel along linear chains of causes. So, we may admit that while Lyme disease is “caused by” Borrelia bacteria, the “deer tick” that spreads the disease is also partly at fault. Similarly, although malaria is caused by a protozoa, the most effective prevention is to reduce the mosquito population or to use netting to keep the mosquitos from biting people. Similarly, you might try to prevent Lyme disease by wearing light clothing, using spray to keep the ticks off, checking for ticks after being in tick infested areas, etc. So, even in common practice, we realize that saying that the little organism causes the disease is an over-simplification.

Once one “gets” a disease, however, the most commonly invoked metaphor is war. We know what the enemy is and we must destroy it! I grant you that is one approach that can be very effective, but consider this. The “human” body contains approximately as many bacterial cells as human cells. What you think of as your “human” body is only half human! It is half bacteria! Furthermore, since we all have trillions of bacteria in us when we are well, the picture of treating bacteria as an enemy to be destroyed is at best an over-simplification. In fact, more recently, medical science seems to indicate that under-exposure to bacteria in childhood can make you more not less susceptible to disease. If you use anti-antibiotics to “destroy” the “enemy” bacteria in your body, many of the “good” bacteria necessary for digestion are also destroyed. This sometimes, though rarely, requires exotic treatment to return to health.

In cancer, both doctors and the general public mainly think of the cancer cells as “enemies” who must be destroyed! And yet, it seems that people may often have mutations that could lead to cancer but don’t. There are even very rare cases of spontaneous cures of cancer. What are some alternatives to thinking of cancer as an “enemy” that must be destroyed?

Clearly, I don’t know of a definite answer or you would have already heard about it on the news! But let’s consider a couple alternatives. First, instead of thinking you have to “destroy” this enemy, imagine you thought of cancer cells as confused. People get confused all the time. Sometimes, we put them in jail. Sometimes we put them in mental hospitals. Sometimes, we simply teach them what they need to know. Sometimes, we do end up killing them. But it is not our approach to kill someone just because they make a mistake. So, we might seek a way to “re-educate” cancer cells so that they “realize” that they are part of something even larger and more wonderful – the human body! How would one go about this? Using the metaphor of a confused person, we would have to understand just why they were acting confused. Then we would have to provide situations so that they could learn (or re-learn) what they needed to know in order to become a productive member of “society.” We could “remind” a liver cell that, after all, they were born to be a liver cell and they’re potentially quite good at that. We could think of cancer as cells that are misinformed or have amnesia about their true nature.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

We might also think along a different line. We could try to discover the best possible environment for these cancer cells to thrive – and then offer it to them somewhere else. For example, perhaps they really prefer an extremely acidic environment. Say you have a skin cancer on the back of your hand that thrives in a really acidic environment. You provide a gradient of acidity next to the tumor and encourage all those acid-seeking cancer cells to migrate into a really acid tube that is next to the tumor. The farther away it gets from you, the more acidic the environment.

You might also think of cancer cells as being rebellious. For whatever reason, they “feel” as though they are not experiencing enough of the “good life” being part of your body so they “take matters into their own hands” and begin leading a rebellion of cells out to steal the food supply and multiply in an unrestrained fashion. A solution might be to “convince” them that they are better off retaining their initial function rather than becoming a lawless gang of cells. I am not sure what the best metaphor for thinking about infection or cancer is, but surely it is worth imagining others rather than sticking to just one based on war as a metaphor.

Business is a Sport.

I treat this at greater length in The Winning Weekend Warrior, but the basic idea is simple. Yes, there are many strategies and tactics from sports that apply to business. But there is at least one crucial difference. Sports are designed to be difficult. They typically require skill and training if you are to do well. The parameters of the sport are fixed at any given time though they will vary somewhat over time. In golf, for instance, the hole is small and the distances are great. Though the rules of golf are complex, there is one over-arching principle. If it would help you to do something, doing that thing is penalized!

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

If golf were a business, many CEO’s would nonetheless approach it as a sport. They would try to hire the “best people” – that is, people with a proven track record of good golfing. They would then proceed to offer incentives for people to do even better. If people shot a high score repeatedly, they would be fired. Eventually, such a CEO might get good results by having skilled people who are well motivated and well trained. But why? If putting a golf ball in the hole is what gained you profit, simply shorten the fairways, widen the hole, and eliminate the hazards! Of course, as a sport this would make golf no challenge and no fun. Everyone could win. But having everyone win is exactly what you should do to maximize profit. Yet many in management are so taken with the “business is a sport” metaphor that they do not change the situation. Some do “change he game” and with spectacular results. Google and Amazon come to mind.

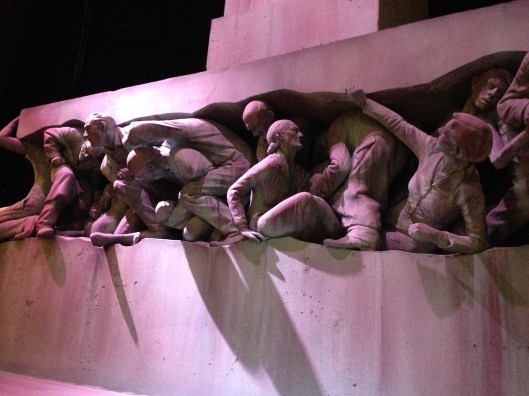

Politics is War.

If you belong to a political party and believe the “other” party or parties are enemies to be destroyed, you are failing to understand the dialectic value that parties with different views can bring to complex situations. Life is a balanced dance between strict replication and structure on the one hand, and variation, exploration, and diversity on the other hand. A species who had no replication of structure from one generation to the next would die off. But so too would a species that had no variation because the slightest change in environment would also cause the species to die off. So it is with human cultures. If every generation had to start from scratch in determining what was edible, how to get along, how to avoid predators and so on, humans would have died out long ago. On the other hand, if a culture were completely unable to evolve and change, they would also die out. Typically, “conservative” parties want to keep things the same for longer and “liberal” parties want to change things more quickly. There is no obvious answer here. But what is vital is that members of each party see that there is value in the debate; in the dialogue; in the dialectic.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

The other party is not an enemy; it is the balance so that you can do what you do best. If you are predisposed toward exploration, science, new experiences, and so on, great! On the other hand, if you are more predisposed toward tradition and loyalty and repetition, great! If you did not have the people of the opposite predisposition, you would have to incorporate all that within yourself. Conservatives are what allows liberals to be liberal. And liberals are what allows conservatives to be conservatives. A huge problem arises, as it has recently in American politics, when one party decides they are just “right” all on their own and “victory” is worth lying, cheating, and stealing to get it. This is not unique to contemporary America of course. History is littered with administrations who were so convinced that they were “right” that they wanted to destroy all opposition. It has always ended badly. Politics is not war. (Though the failure of politics often leads to war.)

UX is All that Matters vs. UX Does Not Matter. Development is war!

As you might guess, neither of these extreme positions is useful. Price matters. Time to market matters. Marketing matters. Having good sales people matters. Having excellent service matters. Having a good user experience matters. It all matters. Depending on the situation, various factors matter relatively more or less.

(Original artwork by Pierce Morgan)

As in the case of political ideologies, it is just fine for UX folks to push for the resources to understand users more deeply; to test interaction paradigms more thoroughly; to collect and observe from more and more users under a wider variety of circumstances. Similarly, while you are pushing for all that and doing your best to argue your case, remember that the other people who are pushing for tighter deadlines, and more superficial testing are not evil; they simply have different perspectives, payoffs, and responsibilities. Naturally, I hope the developers and financial people do not view UX folks as simply “roadblocks” to getting the product out quickly and cheaply either.

The first half of 2018, I tried to catalog many of the “best practices” in collaboration and teamwork. You might find some of these useful if you are embroiled in “UX wars.” You and your colleagues from other disciplines might also find it useful to consider that it is worth taking the time to affirm your common purpose and common ground. You are meant to work together. Development is not war!