Growing up in the semi-developed neighborhoods I did, we never had enough kids of the same age to play football, baseball, or even basketball with full teams. One upside of that was that we played modified games according to how many people showed up. For example, we often played basketball one on one or two on two. More rarely, we played three on three. One common variant of baseball we called “Three Dollars.” One person batted by throwing the ball in the air themselves, then quickly positioning that throwing hand onto the bat in order to hit the ball. The other two, three or four players were “fielders” and if they caught a fly ball, they would receive “$1.00.” If they caught it on the first hop, it was $.50 and a deftly caught a grounder netted you $.25. In effect, this was just a way to keep score. No money ever actually changed hands. Whoever earned at least three dollars, then got to take the batter’s position. In my experience, everyone would rather be the batter than one of the fielders. Anyway, fielders also lost this symbolic money. If you went for a fly ball and dropped it, you lost a dollar. Similarly, you would lose money for bobbling a one-bouncer or grounder. This game seemed to be pretty well-known throughout America so I’m sure we didn’t invent it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_baseball

However, we did try tweaking the rules. For example, we sometimes played without the penalty clause. You gained but never lost “money.” But we decided to go back to the “original” rules. Then, another time, we decided to try it with a different goal, five dollars. After we tried that a few times, we all agreed it took too long to get a turn at bat. So, again, we returned to the original rules. Another slight variant that came up was that not all fly balls were equally difficult. On the one hand, a sharply curving rocket line drive is very difficult to grab! A blooper fly ball is easy; in fact, easier than many grounders. On the other hand, for us at least, a towering fly ball was again quite difficult. So, we experimented with awarding various amounts such as $.75 for an easy blooper but as much as $1.50 for a sharp line drive. It proved that there were too many “boundary cases” to make this a pleasant way to spend an afternoon. None of us really wanted to waste time arguing instead of playing baseball! That was the sort of nonsense that parents engaged in, but kids were smarter than that. On the other hand, each of us instinctively knew that we also had to “stick up for ourselves.” We could not just acquiesce in the face of injustice. Quite naturally, we would tend to see things a bit differently. Let’s say I am in the outfield and have $2.00. Now, you, as the batter, hit a looping fly ball/line drive which curves and sinks. I make a nice catch. Yay me. But now I start trotting up to the plate because $2.00 plus $1.50 for a line drive puts me at $3.50 and it’s my turn to swing that sweet honey colored bat and knock that little ball for a loop. But you say, “Whoa! Hang on there, John. You only have $2.75!” And I say, (and, please note that there is no baseball going on during this exchange) “No way. That was a line drive! That was a hard one too!” (And, I mean that in the sense that it curved and sank and it was actually quite a hard catch to make.) So, then, you say, “What? That wasn’t hard! I caught a lot of line drives that were harder than that one.” (And, what you mean by “hard” is that it was high velocity.) Generally speaking, we resolved these disputes but after 3 or four of them, we made a firm decision to revert to the original rules. In an entire season, under the “normal rules”, there might be one questionable call as to whether a ball was caught at the very end of the first bounce or just after the second bounce began. But the categories of fly ball, one bounce, two or more bounces — these withstood the test of time.

Learning by modeling; in this case by modeling something in the real world.

There are some interesting balancing acts inherent in the “design” of these rules. I am positive that this game was not invented by a single individual who used a mathematical algorithm to determine the appropriate “values” for the various fielding plays and what the stopping rule was and whether or not to extract penalties. Kids tried out various things and found out what “worked.” The rules and the consequences were simple enough (and easily reversible enough) for our small group to determine what worked for us. For example, if we make the changeover goal dollar amount too little; e.g., $1.50, the turnover is too fast. Too much time is spent running in to take the bat one minute and then running back out again later to field. No-one gets to “warm up” in their position enough to play their best. To the batter, if feels like a real win to be able to hit the ball and, in a way control the game. Because, any half way decent batter, if they are hitting from their own toss can easily direct the ball to left, center or right field and can determine whether they are hitting a likely fly ball, one bouncer or grounder. So, for my own selfish reasons, I wanted the game to go as long as possible with me as batter. So, it made sense to hit more often to those players who had low amounts so as to “even up” the game. This also made it more exciting for the fielders because it made the game “closer” for them. An unwritten code however, also kept this from getting out of hand. For instance, if I began by hitting two hard line drives to the left fielder, and they made great catches, it wasn’t really okay to simply ignore them and never hit to them again until everyone had caught up.

Many potential rule changes never even came up in conversation. For example, no-one ever said, “Hey, let’s count $.98 for a fly ball, $.56 for a one-hopper and $.33 for a grounder.” We wanted to spend the summer (or at least much of it) honing our baseball skills, not our arithmetic skills. And, while we soon discovered that we did not want to spend our time arguing about the boundary between a line drive and a fly ball, we knew without even trying that we definitely didn’t want to spend our time practicing mental arithmetic. And, we further instinctively knew that people would make errors of addition as well as memory. It was pretty easy for the batters and other fielders to keep track of what three people had when left fielder had $2.50, center fielder only had $1.50 and right fielder had $2.75. No way did anyone want to remember current scores such as, $2.29, $2.85 and $2.95. Then, the left fielder misses a grounder and you subtract $.33 to get to $1.96. No. Not happening.

We wanted rules. We never simply had one person bat as long as they felt like it. And, we definitely didn’t want to argue after every single strike of the ball whether it was time for someone else to bat and if so, who that might be. So, the rules were really helpful! They were simple. They were fair. And they minimized arguments. We experimented with rule changes but in every case, decided to go back to the original rules. And, there were many potential rules that we never even discussed because they would be silly, at least for my neighbors and friends.

In addition to all the formal rules, unwritten and mostly unspoken codes of conduct also impinged upon our play. If someone “had to” bring their much younger sibling along, for example, we didn’t hit a line drive at them as hard as we could. We knew that that wasn’t “fair” even though it was within the rules. Fielders tended to “know” how far each batter could hit a fly ball and positioned themselves accordingly. Someone could have pretended not to be able to hit farther than 100 feet; keep drawing the fielders in and then bang it over their heads so they had no chance of getting a valuable fly ball. But no-one did that. It was understood that you hit the ball as far as you could. Fielders also positioned themselves far enough away from each other so that running into each other’s implicit “territory” proved rare. “Calling for” a ball occurred but not very often. We never had to say, as best I can recall, that you were not allowed to “interfere” with each other’s catches. Implicitly, even though the fielders were competing with each other to take the next turn at bat, the fielders were modeled after a real baseball game and so, in effect, the fielders were all on the “same team” just as they would be in a real outfield or infield.

A number of interesting phenomena occurred around this and similar games but the one I want to focus on now is that we experimented with the rules, we changed the rules, and if we didn’t like the new results or process, we changed the rules back to the way they were. And I find this relevant today because I find that many of my colleagues, classmates and friends seem to want to “return” to a set of conditions that no longer exist. I totally get that and in many ways can relate. It seems doable because many of us have had similar experiences both in sports and in other arenas where we try out a new way of doing things and then decide the old way is better. In my experience, this worked and with very little argument. I don’t recall spending time in my childhood screaming about whether a $5.00 limit or a $3.00 limit was better for the game. We started with a $3.00 limit, tried a $5.00 limit and then we all agreed $3.00 was better. There may well be places where the particular group of kids decided on $2.50 or $5.00 limits. But is there any group of kids who beat each other up over this? Is there even a group of kids who preferred the $2.50 limit who refused to play with the $5.00 kids? I don’t really know, but in my observations of kids whether parental, grandparental; whether familiar or professional; whether at camps I attended or ones where I was a counselor; whether in a psychiatric hospital or a school setting, I have never seen it. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, but it can’t be very common.

In our small group of neighborhood kids, we were able to “roll back” rules pretty easily and smoothly. It seems as though we should be able to do this on a larger scale, but I just don’t think that is possible. It may or may not be desirable for various specific instances, but I don’t think for many situations, it is even possible; or, at the very least, the costs are far higher than we would be willing to pay.

Consider some examples from nutrition. When I was growing up, my parents and grandparents inculcated in me that I was supposed to eat “good” meals which included meat or fish every single day. At some point during my adult life, there came to be concern about cholesterol in the diet. The theory was that cholesterol contributed to heart disease and that you should avoid eating foods like beef, eggs, and shrimp which contained a relatively large amount of cholesterol. Now, we believe that refined sugar and artificial sweeteners are both far worse sources of calories than beef, eggs and shrimp. In fact, most of the cholesterol in your blood is made by you and only a little comes from your diet. But eating a lot of sugar causes you to store rather than burn body fat and also makes your cells eventually “immune” to the regulatory effects of insulin.

Now, people have always had differing tastes when it comes to food. Some people have completely ignored every bit of nutritional advice that’s ever been put out there. They eat what they feel like eating. Others are willing to try any new fad that comes out. Most people are somewhere in between. But because there have always been people eating beef, eggs, and shrimp, repopulating these into my diet or your diet is pretty easy. It is one case where we really can roll back guidelines.

But imagine instead of having a change in nutritional guidelines, we all subscribed to a religion which made eating any birds or bird products strictly taboo for the last thousand years. And, let’s imagine that was true world-wide. Now, a revelation comes that actually, birds are quite good to eat and so are eggs. Now what? There are no chicken farms. There are no boxes made to carry eggs. There are no companies whose business is to provide eggs. There are no egg inspectors. There are no regulations about breeding chickens or gathering eggs. Indeed, it is a lost art. There are no recipes that use eggs or chicken. People don’t realize that some people are quite allergic to eggs. People don’t realize that eggs “spoil” if they are kept warm too long. The point is, that unlike my little coterie of kids deciding to go back to $3.00 instead of $5.00 (which was easy), the adjustment of adding chicken and eggs back into our diets will be a big deal. There will be many mistakes along the way. A few people will even die of food poisoning. Still, my guess is that it would prove possible. The benefits would outweigh the costs. Even so, there would be a lot of disruption. People who sell soy products, for instance, might well claim that the religious revelation was bogus and that eggs and chicken should still be banned. Even people who are persuaded that it is not a sin to eat eggs might still think they are pretty gross because they have been brought up that way. Family stories have been passed down over generations. Perhaps Aunt Sally once tried an egg when she was little and that’s why she grew up cross-eyed. (This isn’t the real reason, but it might be the reason in a family story).

The point is that we can “change” this way of doing things, but it will be much more disruptive than changing the rules of our ersatz baseball game. Other changes are even more difficult to pull off. Partly this is because in a complex interconnected society like ours, any change away from the status quo will hit some people harder than others. Just like our “soy producer” in the egg example, whoever is “hurt” by a reversion to something older will not like it and will struggle socially, politically, and legally to keep things they way they are now. They will not want to go back to how things were (or, for that matter, into a future which is different either).

Most of our ways of doing things are now highly interconnected and global. For example, the computer I am writing on at this moment is far, far, more powerful than all the computing power worldwide that existed when I was ten. While I know something about how to use this computer, I do not know the details of how the hardware works, the operating system, the application that I am using, and so on. This computer was produced and delivered by means of an extremely complex global network and supply chain. The materials came from somewhere on the planet and probably no-one knows exactly where every part of the raw material even came from. The talent that conceived of the computer, designed it and built it was again from all over the world. Apple does business in at least 125 countries throughout the world. Other major companies are similar. The situation is nothing like having 125 separate companies in 125 different countries. These companies are all linked by reporting relationships, training programs, supply chains, communication links, personnel exchanges, and so on. If, for whatever reason, Apple decided to become 125 different independent companies — one for each country, they would, I believe, fail pretty quickly. It would be nearly as difficult (and as sensible) as if you decided that you would no longer be an integrated human person but instead your arms, your legs, your head and your trunk would now operate as six separate entities.

We are now vastly interconnected. Certainly, WWI and WWII were deadly global conflicts. Not only were these wars costly in money and human life, but they were horrendously disruptive as well. Families were broken apart, infrastructure was destroyed, supply chains were interrupted. New hatreds flared. But even as lethal and costly as these wars were, WWIII would be much worse even if no atomic, biological or chemical weapons were used. Why? Because nearly every country in the world is now tightly interconnected with every other country. Maybe that was a great idea. Maybe it was a horrible idea. Maybe it’s a good idea in general, but we should have been much more thoughtful and deliberate about the details of how we inter-relate. Regardless of how wise or unwise globalization has been, we cannot simply “change the rules” back to the way they were 100 years ago.

If we attempt to destroy globalization, and have each country “fend for itself,” it will be incredibly expensive both in dollars and in human lives lost. This genie, however much you hate it or love it, will not squeeze back into that bottle. If we attempt to go back 100 years, we will actually go back about 2000 years. Again, consider this computer I am using. I worked in the computing field for 50 years. And, I would be completely helpless to try to make anything like this computer from scratch. But the computer is far from the only example. Could I fix my car? Some things I could but the engine diagnostics now require a computer hook up. Could I fix my TV? Not much. My dad was an electrical engineer. The most common cause of problems with a TV in my youth was that a vacuum tube stopped operating properly. When the TV was “on the blink” we would take one or more tubes out of the TV and take them to a testing machine at the grocery, drug store, or hardware store and see which tube needed to be replaced and then buy that replacement, go back home, put in the new tube and *bingo* the TV worked again! Can I do that today? No. Can you? I doubt it. But it isn’t simply electronics and automotive industries that are global and complex. It is nearly ever aspect of life: financial, medical, informational, entertainment, sports, and so on. What about your local softball team? You know all those people personally just as I knew the folks I played $3.00 with. But where are you spikes made? How about your softballs? Bats? Mitts? The last bat I bought — a beautiful, heavy aluminum bat — it came sheathed in plastic. I think that was unneeded pollution, but there it was. Where was that plastic made? Where did the bat come from? Where was the metal mined? Where was it fashioned?

Personally, on the whole, I think the highly interconnected world we live in is more fun and interesting. In a typical week, I literally eat food inspired by Mexican, Japanese, Indian, and Thai recipes. In many cases, it is prepared by people originally from those countries. Books, plants for gardens, music, movies, games — these things are made worldwide and distributed worldwide. To me, it makes life much more interesting. If you don’t like globalization as much as I do, you can certainly stick to American authors and “traditional” American dishes (although almost all of them came originally from another country), American composers, etc. You’re missing out, but it’s your call. But no matter how you try, you cannot “disentangle” yourself completely from the larger world.

The inter-connectedness often wreaks havoc as well. Little bits of plastic micro-trash that come from the United States pollute oceans everywhere. Air pollution that originates in Asia comes across the Pacific to affect people in North America. If the Japanese kill too many whales, it affects the ecosystem world-wide. Pollutants that come from Belgium may kill bees in Argentina. A plague that begins in Thailand may kill people in New Jersey or Sweden. We cannot wish this interconnectedness away. Today’s “Citizen Soldier” needs to be smart as well as brave and loyal. You are not standing in a long line dressed in a red uniform facing a long line of soldiers dressed in blue (who are your enemy). You are going about your own business. But you must understand that how you treat people from every other country whether you are visiting a country or they are visiting your country — how you treat them will impact people globally. If you treat people badly it will impact you and your neighbors badly in the long run. We really have to think globally even while we act locally. I think it’s the “right” thing to do. It’s a little hard to imagine a serious world religion or world philosophy that justifies trying to get as much as possible for you or your tight-knit group of friends at everyone else’s expense. But even if you somehow convince yourself that it’s morally “okay” to be a complete isolationist, reality will not let you do it.

You can take your turn at bat. But you also have to go out in the field and take that turn. Kids who take their first turn at bat and then “go home” as soon as they have to go out in the field do not get called upon to play a second or third time. You might most enjoy being a bazooka shooter. But you are going to have to spend a fair amount of your time being “Claude the Radioman” (See earlier blog post) because with seven billion people on the planet, more coordination than ever is needed. It won’t work to have everyone be a “hunter-gatherer” any more. It won’t work for everyone to “do their own thing.” It won’t work to roll back the rules of the last 100 years and have every country do their own thing either. We cannot smoothly “undo” history. We cannot jam the genie of globalization back into the bottle. I have a much better chance of fitting into the pants of my first wedding suit (waist 29”).

I mentioned that in my neighborhood, we typically did not have full teams. One day, however, while we were playing American football (five on five) in a vacant field two blocks down from my house, an older kid approached us explaining that he wanted “his team” to play “our team.” We didn’t actually have a “team” at all. We would get together and chose captains who would then take turns picking kids for their (very temporary) “team” for that particular game. We had a football. That was pretty much the extent of our “equipment” though someone did occasionally bring a kicking tee. The vacant lot did not have any goal posts so there were no field goals. We generally played a variant of American football, wherein the defenders were not allowed to cross the line of scrimmage and tackle the quarterback until they had counted “One Chimpanzee, Two Chimpanzee, Three Chimpanzee, Four Chimpanzee, Five Chimpanzee” — and then, they could rush in and tackle the quarterback. In the five on five variant, the center was generally a blocker while the other three ran down the field and tried to “get open” so that the quarterback could hit them with a pass. Occasionally, a quarterback would try a run. If they could “fake” a pass and get the rusher (usually only one person) to jump up off the ground, the quarterback could generally sprint past them before they got back on the ground and gain a reasonable number of yards before the other defenders realized it was a run. (In case you aren’t familiar with American football, once the quarterback goes beyond the point where the ball was hiked from, they are no longer allowed to throw a forward pass).

http://www.understanding-american-football.com/football-rules.html

In any case, although five on five football was fun, it also seemed to us that it would be fun to play eleven on eleven like “real” American football. So, we agreed to come back the next day after school and face “his team.” Weather cooperated and we showed up the next day after school and so did the other team. In uniform. We didn’t have uniforms. But not only were they all wearing the same colors. These kids had helmets, shoulder pads, thigh pads, elbow pads and shin pads! They were armored! But we weren’t! Every time their center hiked the ball to the quarterback, a bunch of us would try to rush in to get the quarterback. No “one-chimpanzee”, “two-chimpanzee” business now. We were playing real football. And getting real bruises.

I can tell you from personal experience, that it hurt an unnatural amount to run into these other guys but we held our ground any way. It did seem unfair to us but they never wavered or offered to take off their pads or helmets. The first few times were not so bad, but once your body is already bruised, then it does hurt to run into someone with full body armor. I suppose it sometimes seemed equally unfair to Medieval peasants without armor who were attacked by armored knights. Hardly a “fair fight” as we would say. Nor does it seem a very “fair fight” for a little kid walking on some distant jungle path to suddenly have their leg blown off from a land mine. And, I suppose some would judge it an unfair fight for a village of unarmed farmers to have a rocket or drone smash their village to pieces along with many of the men, women, children and livestock. Just guessing, but that’s my sense of it.

This older kid who arranged our game did not actually play, as I recall, but served not only as coach for his team but also as the one and only referee for the game. That didn’t seem particularly fair either, but he was pretty impartial. As it began to get dark though and we were still tied, he did make something of an unfair call, at least in my opinion. Anyway, I think they won by only one touchdown. We did pretty well against these armored kids from another part of town. But we were a sore lot the next day. None of us suffered any major injury such as a broken bone though we were all pretty black and blue from the battering. None of us were very eager to have a rematch though. We talked briefly about the possibility of getting our own uniforms but we were way short of that financially. Even if we had actually collected all the pretend money we talked about in “$3.00” we couldn’t afford that kind of equipment.

Does it matter whether a game — or a war — is a “fair” fight? Or, does it only matter who “wins”? In sports, we generally have a lot of rules and regulations to insure fair play. We would consider it a gross misconduct of justice to have one NFL team denied equipment! Some readers may be old enough to recall the controversy over using fiberglass poles in the Olympics. See the link below for a fascinating story regarding the “fairness” of Olympic pole vaulting.

I think it may matter more than many think as to whether a fight is a fair one. A fair loss leads most people to acceptance and adaptation; in many cases, it can serve as motivation to do better . But if they think the fight is unfair, resentment will often linger and eventually result in another fight. Chances are that this time, the party who feels they had been treated unfairly will no longer care about having a “fair fight” and do anything they can to win. Anything. So, it serves us well to think long and hard about winning an unfair fight. What will happen next? It seems to me that when we win an unfair fight, there are many negative consequences and they almost always outweigh the benefits of the win.

First of all, whoever loses the unfair fight will resent you. Second, people not involved at all in the unfair fight and who don’t even care about the outcome, will care about the process and the vast majority will dislike whoever behaves unfairly. Third, it makes it more likely that other people will be unfair in their own transactions.

In the days of childhood sports, we sometimes disagreed about what was fair. But we never disagreed about whether it was okay not to even try to be fair. We all assumed we were supposed to be “fair.” You must understand, this was unsupervised child’s play. We did not play baseball with parents around coaching, umping, and spectating. Of course, we had disagreements and sometimes we lost our tempers. On rare occasions, someone might walk off in a huff. But, there really weren’t that many huffs to go around back then, so it was rare. And, whoever did walk off in a huff was back the next day ready to play $3.00 again. Their huff dissolved in the cool night breezes. When they went to their closet the next day, no wearable huff remained. There may have been a few tattered huff-shreds in the bottom of the closet, but not even enough to wear as a bathing suit, let alone a three piece suit of huff complete with huff vest, huff pants, and a huff coat. I don’t think any of us even owned a huff tie.

I think part of the reason was that all of our disagreements and arguments were face to face. We never sent e-mail. And, we certainly never hired a lawyer to “represent” us. For some reason, when one person “represents” another, they feel it is more “okay” to do unfair things than the person themselves would feel comfortable with. We kids simply discovered that it was a lot more fun to play baseball, in any of the variants, wearing a shirt, sneakers and jeans. A huff suit was simply too confining and too easily torn. Kids all seem to know this instinctively, but as they grow up, they may begin to fill their closet with huffs and wear them on many occasions.

Imagine a world in which adults all gave their huff suits to the Goodwill. In this world, they talked, solved problems, had some fun, and when they disagreed, tried to do what was fair for everyone. It sounds kind of crazy, I know. But we live in a world of miracles, don’t we? And, that world is embedded in a universe of miracles. Very slowly we are coming to understand more of it. Our understanding of this amazing universe grows and some of that understanding even sheds light on how our bodies and brains work as well as the fundamental characteristics of the universe. Maybe somewhere in this vast universe of miracles, there is a way to experiment with the rules of the game until we find a way that works for everyone who wants to play. Perhaps we could pay $.25 when someone can restate what you said to your satisfaction. If someone can think of another example of the same principle, they get $.50. And, if someone has a brand new sharable insight on the topic, they get $1.00. First one to $3.00 gets to direct the dialogue for awhile. Come dressed for serious play. No huff allowed.

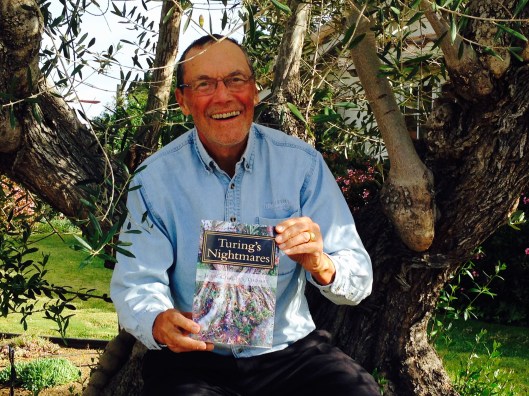

(The story above and many cousins like it are compiled now in a book available on Amazon: Tales from an American Childhood: Recollection and Revelation. I recount early experiences and then related them to contemporary issues and challenges in society).