UCSD: DSGN 90

Day Three: Soliciting Stories from Others.

Any thoughts or reflections on yesterday or on trying to further improve your story? Anything that seems like an “insoluble” problem or dilemma that you want to share with the class?

Introduction: 15 minutes.

Using stories for generating ideas for products.

Wants and Needs. Cite George Furnas; we NEED oxygen but we WANT to avoid build up of Carbon Dioxide. We NEED healthy food but we WANT sugar.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/246277995_Future_design_mindful_of_the_MoRAS

Go for needs whenever possible. Why? Your product or service will be more enduring.

Examples.

Drug Dealers get shot or jailed.

Cigarette companies get sued, fined.

Even the best buggy whip manufacturers are likely to go out of business. If you focus people’s attention too much on what they like and dislike about their current situation, they are likely to focus on their wants: “I want a lighter buggy whip.” “I want a buggy whip that makes a snappier sound.” “I want a buggy whip that motivates the horse without injuring it.”

Don’t be fooled by the words that the user/client/stakeholder uses. They may say, “I need a lighter buggy whip.” They are still talking about their wants. Merely using the word “need” doesn’t make it so.

Theory of Mind. How does this relate to storytelling? How does it relate to eliciting stories from others? Using elements of empathy. Variant on heuristic evaluation: Have evaluators “imagine” using the product or service from the perspective of others.

Guidelines for Interviewing (from Debbie Lawrence). 15 minutes

- Prepare ahead of time. You may want to find out a bit about them, their role, the situation, and prepare some questions you would like to have answered, not as a strict sequential questionnaire for the person you’re interviewing but to remind yourself.

- Thank them for their time. Provide a “warm-up” period.

- Most people do not want to and will not launch into a story that is potentially embarrassing or reveals something negative about their company, a product they use, other people, etc. Of course, there are exceptions.

- Tell something personal and revealing about yourself; perhaps tell a story that is a model of the kind of story you’re looking for.

- Observe an implicit contract of trust.O

- Provide a motivation for the story — why it’s important.

- Say how they, or their colleagues, or people like them, or society as a whole may benefit.

- Accept the storyteller’s story and worldview. Don’t resist the story.

- Don’t problem solve for them. “Why didn’t you simply call the police?” “Why didn’t you read the manual first?” This approach can appear blaming, the word “simply” implies that this is the “obvious” solution. Let them tell the story with as few interruptions as possible. Later, if you want to probe for other actions that they considered, you might ask, “Let’s go back to the part where you broke the guitar over their head. Were there other actions you considered at the time?”

- Reveal who you are, how the story will be used, potential audience and goals, answer questions.

Be honest. If they are exposing themselves, they should know before they tell their story. If true, say that stories will all be anonymized (and make it so.) And anonymized means more than simply changing the name! For instance, a long time colleague of mine at IBM Research was Cathy Wolfe who got ALS and continued to work a IBM Research. If I told about someone at IBM Research who worked in Human Computer Interaction research despite ALS, it wouldn’t be an effective anonymization to simply change her name to Carole Walcott.

- Use questions to probe. Sometimes, a totally “off the wall” question can create space for story to emerge.

This can be especially useful if it seems as though they have told the story many times before. They may be skipping over a recounting of their actual experience and instead recalling the story that they’ve already told.

- Empower the storyteller — they are the expert in their experience!

Avoid statements that deny a person’s experience. “Surely, you didn’t really expect your brother to….” “But everyone knows that you can’t….”

- Avoid threat; don’t appear as an expert yourself.

“I wondered about her actions because I’m kind of an amateur psychologist and so…” “OH, really? I’m getting my degree in cognitive psychology from UCSD in just a few months.” (This may seem like an attempt to find common ground and build rapport; it might work with some people, but others will read it as you trying to “one up” them and to question them on how much of a psychologist they really could be.

- Listen with avid interest.

If possible, and if it doesn’t make the teller uncomfortable, it’s good to go with two interviewers and either record the interview or have another person take notes. When I was training as a Cognitive Behavior therapist, we recorded sessions as a matter of course. I explained what this was for (so I could review it and have my supervisory group review it for suggestions) and said, “Here’s the pause button. If you ever want to say anything and NOT have it recorded, feel free to just hit the pause button.

- Thank them again.

Go over your notes immediately, especially if you have not recorded it.

Small Group Exercise: 3-4 people in the group. Interview each other to gain story. One interviews. One Records. One or two provide feedback for the interviewer. 60 minutes.

Take a moment before beginning to think about some unusual experience, situation, part-time job, summer job, vacation, that you had. Try to recall something that could have gone better – a time you were frustrated, scared, angry, anxious, depressed. Then, use this as a suggestion for what the interviewer asks about. It does not have to be a life-changing experience! Just getting lost on campus, buying a video game and then be frustrated with it, or getting an unfair traffic ticket is enough. Let the interviewer ask you questions about your experience. The interviewers long-term goal is to uncover one or more needs that might be addressed by better design. Of course, you probably won’t get that far in a short interview, but keep that goal in mind.

The Feedback structure should proceed as follows:

- First, the Interviewer says one thing they liked about what they did in the interview and asks for feedback on how they could have done one thing better.

- Second, the observers each say one thing they liked about what the interviewer did and one thing that they thought could be improved for next time.

- Third, the interviewee says one thing that they liked about how the interviewer conducted the interview and provides one suggestion for improvement.

- Fourth, the group briefly discusses whether the interviewer was able to delve into underlying needs or whether it stayed at the want level. Also, discuss whether they interviewer was able to elicit any stories of experiences from the interviewee.

FB for these sessions.

Each interviewer might tell story to larger group as well.

Class discussion about story elicitation lessons learned. 20 minutes.

Review, summary, and preview of homework challenges: 5 minutes.

Questions: 5 minutes.

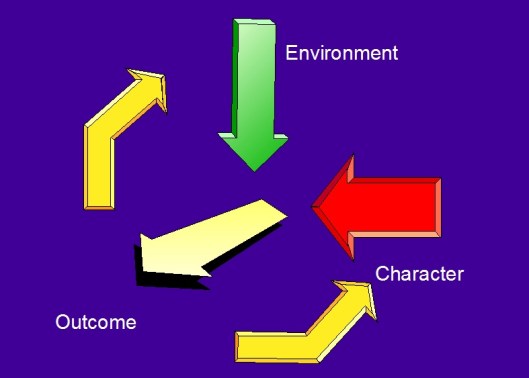

Optional Homework Challenge: Design a high-level visual representation for one of the three major “dimensions” of story: Plot, Character, or Setting. Stories are written or told with words, but the underlying structure is hard to “see” by simply looking word by word. Representations can either make problem solving, including design problem solving much easier — or much more difficult. So, your goal is to provide a thinking tool for higher level design aspects of story. Prepare to give a ten minute talk to the class about your representation on Friday.

Speech analysis and waveform versus spectrograph. Use of “speech-flakes” by Cliff Pickover (which again shows that human beings are not just information processors).

Optional Homework Challenge: Look up the TRIZ method. This was developed by Genrich Altschuller for invention in the engineering domain. Find out his story. Prepare a ten minute explanation of the method for this class. At the end, speculate about how this method might be applied to the process of story design on Friday.

Optional Homework Challenge: Find your own design problem related to story — and solve it. Prepare a ten minute class presentation that poses the design problem and then explains, shows, demonstrates your attempt to solve that problem.

Examples: You do NOT have to choose one of these.

How could a computer program extract the value changes in a story. This could be used, e.g., to check whether every scene had at least one value change (love to not love; rich to penniless; sick to healthy; alive to dead). Or, it could be used if you wanted to search for stories that showed someone going from rich to penniless.

How could you design a program to find stories in a large amount of text — part stories and part non-stories?

How could you provide a tool that would change a story to modify it for different situations, different audiences, or different goals?