Pattern Language Overview

Prolog/Acknowledgement:

An old story recounts a person walking down a path and noticing two workers laying stones and cementing them into place. The walker noticed that one of the workers walked with a bounce in their step and a whistle on their lips. The other worker, however, trudged from stone pile to wall with a scowl. The walker imagined that perhaps the disgruntled worker was being paid less or was ill or had suffered a recent tragedy. Because the walker was familiar with the “Iroquois Rule of Six” however, they knew that it would be better to test their hypotheses than make assumptions about the reasons. He asked the disgruntled worker what they were doing. “Isn’t it obvious? I have to take these stones from the pile over there and lay them in that wall over there and cement them in place.” When asked the same question, the worker with the sunny disposition answered, “Isn’t it obvious? I’m building a cathedral!”

Many years ago, I read in IBM’s company magazine, Think, about a training program that IBM had provided in Kingston for people working in their chip fabrication plant. Management had decided to give an overview of the entire process to the assembly line workers. According to the story, one older worker jumped up in class and yelled, “Oh, NO! I’ve been doing it wrong! All these years!” Upon questioning, it turned out that the worker’s career had been in inspecting masks. Each mask was, in turn, used to make tens or hundreds of thousands of chips. Since so much effort went into the making of a mask, the worker had always thought it would be counter-productive to toss out masks that only had one or two flaws in them.

Astronauts who see the earth from space see things in a new and different perspective. In some cases, it causes them to better see the inter-relatedness of all nations and the desperate necessity of working together to ensure the ecological viability of the earth.

These stories illustrate that an overview, map, or vision can serve two important purposes in collaboration and coordination. First, it can serve as a motivation. Who wouldn’t rather be building a cathedral rather than merely moving stones? Second, an overview can inform people about how their work interacts with the work of others and thereby allow them to make choices that positively impact the project, product, or campaign as a whole.

I’m talking a pause from posting specific Patterns to provide a preview/overview of the proposed Pattern Language on “best practices” for teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and cooperation. There are many things that have caused me to believe we need such a Pattern Language. Among them, the most important reason for me is the recent up-tick in uncivil communication and in turning nearly every single human activity into a “competition.” I’ve also seen a continued misuse of the biological metaphor that evolution proceeds by fierce competition. Of course, competition is important in evolution. So is cooperation. So, I argue, is individual choice (See blog post: “Ripples”.)

This Pattern Language is still a “Work in Progress” so I cannot yet give a highly coherent and motivating overview, but I hope this list will at least give some better notion of where this project might be heading. I briefly summarize the Patterns for the first two months of 2018 and to preview some upcoming Patterns by presenting only their essence. Providing this overview is itself attempting to make use of a Pattern – “Provide a Motivating Map.” As you read through a larger number quickly, I am hoping that you will begin to see that these Patterns are not a set of independent disconnected parts but more like an inter-connected web of ideas. There are, I believe, a number of different ways to organize this web for particular purposes. More on that later, but so far, I have thought of at least two ways to categorize the Patterns.

First, the Patterns could be categorized into four basic classes of human needs; 1) to acquire new things or experiences, 2) to defend, 3) to bond, 4) to learn. Often a large scale human activity may have 2, 3 or even all 4 of these as goals. But, at least in terms of the focus of current activity, one of these predominates. I would argue that when having a Synectics session (a kind of structured brainstorming), the primary goal is to acquire new ideas or solutions. It may result in a product that “defends” a company’s position in the marketplace; it may well increase social bonding in the group; and participants will almost certainly learn something. But, the most relevant Patterns to the situation at hand are those whose primary purpose is to better acquire things. The primary purpose of Meaningful Initiation, however is social bonding.

A second way of categorizing the Pattern is in terms of the current stage of development of a product, service, or work one is currently in. If you are engaged in problem finding, or problem formulation, Bohm Dialogue is particularly well-suited to the current task at hand. After Action Review, however, is better suited to looking back at or near the end of a project, development, construction, or campaign. There are no hard and fast boundaries implied. These are heuristics meant to help deal with the complexity of an entire Pattern Language. One could use a slightly altered After Action Review as a jumping off place for new product idea generation. Instead of asking, “What could we do better next time to avoid making error X?” you could ask instead, “How could a mobile phone app be used to help make sure people would avoid making error X?”

A third thing to note about Patterns, is that they form an inter-connected lattice. They are not a strict hierarchy, but some Patterns are higher level than others. A higher level Pattern may have lower level Patterns as components or as alternatives. Two high level Patterns are: Special Processes for Special Purposes and Special Roles for Special Functions. Some alternatives for special purposes are Synectics for generating alternatives and stimulating divergent thinking, the K-J Method of Clustering, and Voting Schemes for prioritizing ideas to pursue. Some examples of various alternative roles include Moderator, Facilitator, and Authority Figure.

Author, reviewer and revision dates:

Created by John C. Thomas on First of March, 2018

Already Published in January – February.

Who Speaks for Wolf?

Make sure to hear from all relevant stakeholders and areas of expertise (or their able proxies).

Reality Check.

For convenience, we often use an ersatz measure that’s somewhat correlated with what we are really interested in because it’s easier. In such cases, you must check to insure the correlation is still valid.

Small Successes Early.

We like to jump right into large, complex tasks. When this is done with a large group of people meant to work smoothly on a large project, it is counter-productive. Instead, begin with a task that is fairly easy, fun and/or relevant and fairly assured of success.

Radical Collocation.

When problems are complex and the sub-parts heavily interact in unpredictable ways, it is worth having the entire group work in very close proximity.

Meaningful Initiation.

When done properly and meaningfully in the right context and controlled by appropriate Authority Figures, initiations may increase group cohesiveness.

The Iroquois Rule of Six.

Human behavior is very tricky to interpret. When you observe behavior, and generate a reason for that behavior, before acting, generate at least five more plausible reasons.

Greater Gathering.

Periodically and/or on special occasions, everyone should have a chance to get together with all of their work colleagues(and in some contexts, their families) and have some fun.

Context-Setting Entrance.

It really helps social interaction if people know what is expected of them. The entrance, metaphorical or physical, can serve a vital role in setting the mood, tone, and formality of the upcoming social interaction.

Bohm Dialogue.

Let someone speak. Listen to what they say without rehearsing your own answer. Reflect on what they say. Share your reflection. A Dialogue seeks to create some shared truth without setting into “sides” or “camps” or judging each statement made on the basis of what it means for me.

Build from Common Ground.

People all share tremendous common ground even across the entire globe. Yet, we often try to jump into resolving our “differences” without first re-affirming what our common ground is. That’s a mistake. Start with discovering common ground and build from that.

To Be Elaborated On:

Use an Appropriate Pattern of Criticism.

For example: first, ask the person for positives and how they could improve; then, ask their peers for the same; then, the Authority Figure adds their feedback in the same order.

Negotiate from Needs, not Positions.

Win/win solutions are much more likely if people negotiate from their needs than from positions. Example: Two sisters fight over the single orange. They both say they want it. At last they compromise and split the orange in half. Neither one is completely satisfied nor dissatisfied. Had they been honest about their real needs, they would have discovered that one wanted the peel for a cake flavoring and the other wanted to eat the fruit inside.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvard_Negotiation_Project

Give a Sympathetic Read.

Natural language is incredibly ambiguous and vague. A reader should take a “sympathetic” stance toward what they read (or hear or feel). Instead of trying to find the “holes” in someone else’s arguments, first try to interpret it so that it does make sense to you.

After Action Review.

After a significant event takes place, parties who were involved in the decision making, should all get together with appropriate facilitators to see what can be learned from the situation. This is neither a “witch hunt” nor a “finger-pointing exercise” but an opportunity to see how to improve the organization over time.

Positive Deviance.

(From book by the same title). The idea is that in any complex situation that you might want to “improve” or “fix” there are some who are in that situation and have already figured out how to succeed. Instead of designing and imposing a solution, you can find out who the success stories are, observe what they are doing, get feedback from the observed and then encourage the success stories to share what they do with the larger community.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive_deviance

Provide a Motivating Map.

Everyone would rather help build a cathedral than simply lay stones atop each other. It’s more motivating to see that you are building something greater than the sum of its parts.

Provide an Overview Map.

The purpose of this map is to let people understand how their particular tasks fit into the grand scheme. This proves useful in many situations. Sometimes, the same Map can serve both as an Overview and Motivating Map.

Collaborating Music.

There is value to be gained in terms of social capital with listening to common music, more in dancing to common music and more still in the creation of common music. Of course, many collaborative activities can create social capital, but music seems to be one of the most “whole-brain” experiences we have and is particularly well-suited to building social capital.

Making Music Together

Narrative Insight Method.

People exchange and build on each other’s stories in specified ways to create and organize insights and lessons learned.

Elicit from Cultural Diversity.

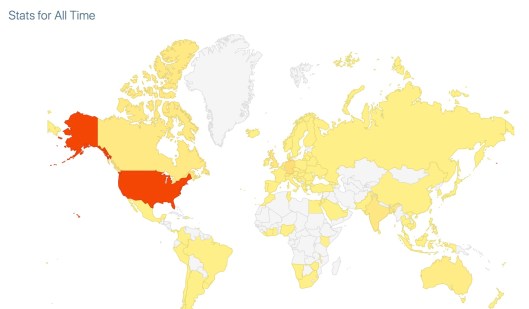

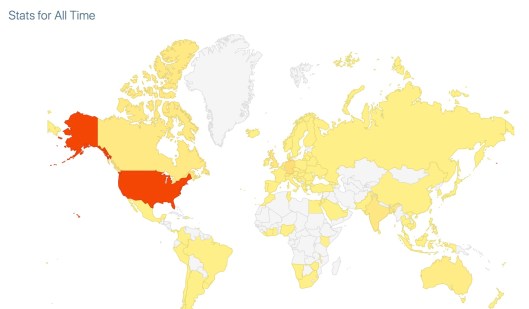

Empirical research shows that more diverse groups can produce more creative and innovative outcomes. Even if such a group cannot work together always, at least use this during divergent thinking, though there is value in diversity for convergent thinking as well. Below is a (badly distorted) map of the world showing the nations from which readers of this blog hailed so far. (Invite your friends from all over the world!)

Help Desk Feeds Design.

(I really want a more general title.) People who work at “help desks” are under time pressure but there should be mechanisms in place for what they learn about customers, tasks, contexts, pain points, to be fed back to development. In a similar fashion, in any domain, whatever information is garnered from interacting face to face with uses, customers, stakeholders, friends, enemies should be fed back to people who design systems, services, products, or governance.

Queue of Communicating Peers.

In many instances, people in queue, whether physical or electronic, share certain concerns in common. (There is always common ground). Rather than have them “stand in line” staring at the back of someone else’s head, encourage them to help enhance mutual understanding among the group.

Palaver Tree.

This name comes from some places in sub-Saharan Africa where people from a village gather to respectfully discuss what concerns the whole village. Generally, this is near a big tree that can provide shade during dry seasons. In colder climates, a communal fire can serve as the focal point. There may be other special places that are conducive to this kind of Dialogue.

Click to access jbe-thesis.pdf

Talking Stick.

Often, when confronting a problem that is pressing, complex, or anxiety-provoking, everyone wants to talk at once. No progress is made because people cannot even hear what is being said in the resulting din and no-one is paying attention to anything but getting their own point heard. A Talking Stick provides a visible cue as to who “has the floor.” Only one person at a time can hold the Talking Stick and only they can talk.

Round Robin Turn Taking.

In a group, it often happens that a small group of people tend to “monopolize” the discussion if it is held in a free-wheeling manner. An alternative is to have an Authority Figure or Moderator or Facilitator make sure that every person gets a chance to speak and that every person, including the shiest are encouraged to give their perspectives.

Mentoring Circle.

It is often easiest for us to learn from people who have recently faced and solved the same problems that we are now facing. A Mentoring Circle provides a way for people to learn from other individuals and from the group.

Levels of Authority.

As one becomes more experienced and more trusted by a group, it is normal to grant more authority to that person to act on behalf of the group and to have more access to its resources.

Anonymous Stories for Organizational Learning

Often individuals make errors that can provide a learning experience, not only for them, but for others as well. Unfortunately, the competitive nature of many organizations makes admitting to errors costly for the person who made the mistake. An anonymized story can provide a way for the organization as a whole to learn from individuals without their accruing blame and ridicule.

Registered Anonymity.

In Amy Bruckman’s MIT dissertation (Moose Crossing), she provided a space for middle school kids to teach each other object-oriented programming. She wanted to make sure the kids “behaved” appropriately despite their being anonymous and on-line despite the fact that these conditions often spawn inappropriate and even mean-spirited comments. While using real identities could help prevent that, it could also lead to even worse behavior. Instead, she used Registered Anonymity. That is, she knew everyone’s real identity and made it clear that inappropriate behavior would not be tolerated. But the child participants were not allowed to share their real identities.

Answer Garden.

People are busy and don’t want to answer the same simple question over and over. In Answer Garden, developed by Mark Ackerman for his MIT dissertation, people with expertise claimed a part of the tree of knowledge that they were familiar with and agreed to answer questions about that specific subject area. Once the question was answered however, newcomers were expect to first look through the tree for the answer they needed. If there are no appropriate answer, they would post their question at the nearest node to the requested answer. The expert would come by and answer that question, not only for the person who initially asked it, but the tree would grow with that newly posted answer as well.

Community of Communities.

Complex wide-ranging problems such as ensuring that the world economy is organized to sustain the ecosystem require many people to address various problems. While a very large group of people may be concerned that they leave a livable planet for their descendants, everyone cannot work on every aspect. Better is to have communities work on those aspects for which they have particular interest and expertise. In Sweden, for example, Karl-Henrik Robert (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl-Henrik_Robèrt) developed a program called “The Natural Step.” This led to the development of specific communities aiding in the way they best could; e.g., lawyers for a sustainable Sweden might concentrate on legislation and regulation, psychologists for a sustainable Sweden might concentrate on methods to raise public awareness; traffic engineers for a sustainable Sweden might concentrate on making more efficient kinds of roundabouts.

Special Roles for Special Purposes.

Every culture seems to have developed this notion. There are many specific roles that have been developed for specific purposes. Below are just a few.

Master of Ceremonies.

This is literally someone in charge of a ceremony, ritual, or rite. It has come to include an entertainer who serves to welcome guests and introduce them. A closely related concept is the “Session Chair” who introduces speakers, makes sure they have what they need, keeps track of time, and moderates audience participation.

Storyteller

In many oral cultures, one person, often chosen because of interest or ability, is chosen to memorize and repeat the oral history. In such cases, the role typically lasts a lifetime, not just a project.

Stake Warrior

The idea of a “stake warrior” is that they literally pound a stake into the ground and then tether themselves to that stake during battle. They can advance, go laterally or retreat, but only so far. Conceptually, a stake warrior shows some flexibility in discussion or negotiation, but there are boundaries beyond which they refuse to go.

DeBono’s Colored Hats.

Edward DeBono has written a number of books about creativity and innovation. One of his ideas is to use colored hats either physically or conceptually to signal which role a person is speaking in. For example, a person wearing a Black Hat is judging ideas while a Green Hat is more for creativity and provocation. More empirical research is needed to validate whether using hats (even metaphorically) actually improves performance.

Moderator

A Moderator’s main job is to make sure that a group actually follows whatever rules it has set out for itself about time limits, civility, taking turns, etc. A Moderator may also adjudicate disputes between two sides.

Facilitator

A Facilitator’s main job is to keep the group moving forward. They might, for instance, suggest a different way of looking at a topic, or try to invoke a metaphor or to draw out less forthcoming group members.

Setting Expectations.

Promise a person five dollars and give them ten. They will be very happy. Promise another person twenty and give them ten. The will be unhappy about it. What’s different? They both get ten dollars. Many books on developing projects will recommend “under-promising and over delivering.” In some cases, because of science fiction, TV programs, and the popular press, people may come to think anything is possible.

Support Flow and Breakdown.

When designing a new system, there is an anticipated way for it to work, whether it’s traffic flow in a city, water flow in the plumbing or information flow in an organization. However, eventually, there will be breakdowns in any of these systems. Breakdowns are always a hassle, but they will be far less so if the possibility of a breakdown has been anticipated ahead of time and then planned for.

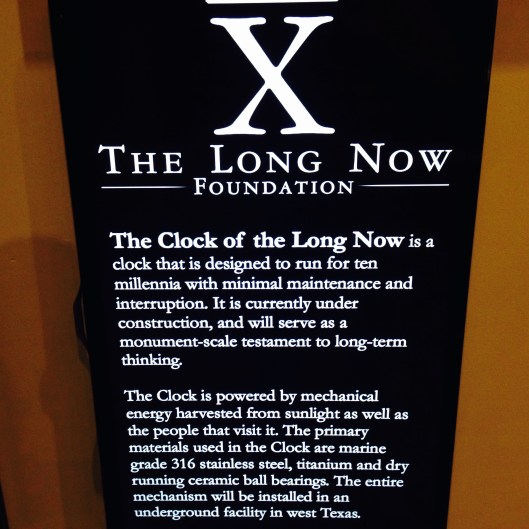

Ratchet Social Change with Infrastructure.

Social changes are initially subject to falling back into previous patterns. In some cases, it may help make a social change more permanent by creating an infrastructure that supports the new system. For instance, if you want to improve relations between two countries, you could fund projects jointly that have a long completion time. Or, if you wanted to divide people, you could make it harder for people to see news and information from people across that divide.

Authority Figure.

Sometimes, a decision needs to be made quickly. Or, perhaps consensus will never be reached. In such cases, it is sometimes useful to have an agreed upon Authority Figure who can be trusted to make an informed decision that takes into account all the relevant interests. Naturally, Authority Figure who makes decisions from a position of ignorance or self-interest must be removed as quickly as possible.

Celebrate Local Successes Globally.

Often a very large-scale collaboration project such as developing a new product or service, governing a country, or trying to manage a cross-cultural non-profit stands to lose coherence and motivation when compared with a small co-located team. One way to help both with organizational learning and with encouraging high spirits is to celebrate local successes with the global team. If done correctly, this can be motivating for both the successful team members and the larger team.

Special Processes for Special Purposes.

This is another high level Pattern. People have developed numerous special purpose processes. Below I review a few. The reason for having different processes for different purposes is that a process can take into account the number of people, the type of goal, the time constraints, and other conditions so that a process is particularly likely to help insure success. A process can fail if it is badly executed but it can also fail simply because it is not appropriate to the task at hand.

Synectics.

Originally, the term derived from the work of Prince and Gordon as a way to describe a suite of techniques for creative problem solving. It is similar to brainstorming in that the emphasis is on generating many ideas quickly and without taking time out of idea generation in order to evaluate and debate each idea. Also like brainstorming, people are encouraged to build on each other’s ideas. In addition, they describe various clever ways to incorporate metaphorical thinking into the process. They also allow each person to work on the “Problem As Understood” and this can be slightly different for each person. I have personally found synectics to be extremely useful. It “works” in generating many ideas, some of which can be quite useful and novel. For example, many years ago, I facilitated such a session and the foreign equivalent of the American IRS decided that increasing tax revenue was their goal but that to achieve that, there were other methods than increasing tax rates and increasing compliance.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synectics

Speed Dating.

Although there are actual speed dating venues, here this term refers to a way for a moderate sized group of people to get to know each other quickly by spending two minutes with one other person in the group quickly recounting their backgrounds and interests and then moving on to form new pairs.

KJ Method.

This is a way to cluster ideas. Many people are now familiar with this as a way of clustering ideas from a brainstorming or synectics session or for clustering ethnographic observations in order to later address product features and functions to address them. Basically, a large number of post-in notes are put on a wall and re-arranged by the group, some of whom may focus on a particular area of the overall cognitive map that is being build or spend their time thinking more about the whole. This method is often used, for example, in CHI Program Committee meetings to take a first pass at developing sessions. There have also been attempts to automate such processes.

Rating and Ranking.

Often a large number of ideas are generated but the resources available do not allow all of them to be pursued. Therefore, a variety of voting, ranking and rating systems have been developed so that the group as a whole has input into the direction taken.

Incremental Value.

It is difficult for people, either as groups or individuals, to move from a current way of doing things to a new one. Almost invariably, people will find the old way of doing things more “comfortable.” The transition to a new way will be much easier if there are incremental improvements in performance along the way rather than the mere promise of some wondrous new state at the conclusion of a long process of change.

Jump Start.

Sometimes, change in an organization or process needs to be “jump-started” by providing additional incentives or special organizational support in some way.

Active Reminders.

As people are learning new methods, processes, and skills, it is helpful to have Active Reminders so that people are less likely to fall into old habits. For example, in attempting to do brainstorming, many people find it very difficult to withhold judgment and criticism from ideas that others put forth. It can be helpful in such cases to have the “Rules” of brainstorming prominent displayed or to have someone whose role is mainly to remind people to build on each other’s ideas when someone critiques an idea.

Controlling Growth.

While people often want their company, non-profit, or movement to grow as quickly as possible, growth without restraint is often called “cancer.” Growth needs to be controlled so that unanticipated side-effects do not destroy the entire company, non-profit or movement. People Express Airlines, for instance, is often thought to have have tanked because their success led to such rapid growth that they could not sustain what made them successful in the first place.

Expressive Communication Builds Mutual Trust.

Studies of cooperation in games such as the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” show that when people communicate something personal and apart from the game such as sharing photos, backgrounds, hobbies, etc. it tends to increase the chances of cooperation.

These Patterns (or really, more accurately, hints of Patterns, are not meant to be exhaustive. But hopefully, there are enough Patterns in this post to give readers a better idea of the wide variety of Patterns than might cohere into a Socio-Technical Pattern Language for Collaboration and Teamwork.

References:

https://socialworldsresearch.org/sites/default/files/j-ag.final-fmt.pdf

https://www.cc.gatech.edu/fac/Amy.Bruckman/thesis/

Fincher, S., Finlay, J., Green, S., Matchen, P., Jones, L., Thomas, J.C., Molina, P. (2004) Perspectives on HCI patterns: Concepts and tools. Workshop at CHI 2004, ACM Conference on Human Factors and Computing Systems.

Pan, Y., Roedl, D., Blevis, E., & Thomas, J. (2015). Fashion Thinking: Fashion Practices and Sustainable Interaction Design. International Journal of Design, 9(1), 53-66.

http://www.it.bton.ac.uk/staff/lp22/HF2000.html

Schuler, D. (2008). Liberating Voices: A Pattern Language for Social Change. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Thomas, J. C., Kellogg, W.A., and Erickson, T. (2001) The Knowledge Management puzzle: Human and social factors in knowledge management. IBM Systems Journal, 40(4), 863-884.

Thomas, J.C. and Carroll, J. (1978). The psychological study of design. Design Studies, 1 (1), pp. 5-11.

Thomas, J. C. (2012). Patterns for emergent global intelligence. In Creativity and Rationale: Enhancing Human Experience By Design J. Carroll (Ed.), New York: Springer.

Thomas, J. C. & Richards, J. T. (2012). Achieving psychological simplicity: Measures and methods to reduce cognitive complexity. In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook. J. Jacko (Ed.) Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Thomas, J.(2008). Fun at work: Managing HCI from a Peopleware perspective. HCI Remixed. D. McDonald & T. Erickson (Eds.), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thomas, J.C. (2003), Social aspects of gerontechnology. In Impact of technology on successful aging N. Charness & K. Warner Schaie (Eds.). New York: Springer.

Thomas, J. C. (2001). An HCI Agenda for the Next Millennium: Emergent Global Intelligence. In R. Earnshaw, R. Guedj, A. van Dam, and J. Vince (Eds.), Frontiers of human-centered computing, online communities, and virtual environments. London: Springer-Verlag.

Thomas, J.C. (1996). The long-term social implications of new information technology. In R. Dholakia, N. Mundorf, & N. Dholakia (Eds.), New Infotainment Technologies in the Home: Demand Side Perspectives. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Thomas, J.C., Lee, A., & Danis, C (2002). “Who Speaks for Wolf?” IBM Research Report, RC-22644. Yorktown Heights, NY: IBM Corporation.

Thomas, J. C. (2017). Building Common Ground in a Wildly Webbed World: A Pattern Language Approach. PPDD Workshop, 5/25/2017, San Diego, CA.

Thomas, J. C. (2017). Old People and New Technology: What’s the Story? Presented at Northwestern University Symposium on the Future of On-Line Interactions, Evanston, Ill, 4/22/2017.

Bohm Dialogue

Bohm Dialogue