The Void

While all the previous properties of natural order seem positive, clear, and obvious, this one seems mildly scary. It reminds me of death, somehow. It’s true that individual death is part of the overall reality of life, it still seems scary. It’s reminiscent of whirlpools, caverns, the abyss. I suppose some of our tiny distant ancestors may have faced the dark mouth cavity of a large predator — a shark, a cave bear, a saber toothed tiger. And a few of those who were terrified enough to flood their bodies with adrenalin may have escaped to reproduce and pass on the terror of utter darkness genes to their offspring, including me.

In a friendlier interpretation, the void could be thought of as “empty” space, or more accurately, extra space not filled with functional items. From that perspective, The Void promotes rest, relaxation, rebirth, regeneration. Your day should include “The Void” in terms of activity — sleep, certainly, but also times that are unscheduled and restorative. If you are scheduling a day long meeting and every minute is accounted for ahead of time, there is no “margin” for something which catches the passion of participants to spill over. There is no time for unanticipated contingencies or for people to reflect on what is happening.

Similarly, a space (whether computer memory or physical space) that is completely “taken up” with data or things becomes inflexible. In extreme cases, nothing can be done because there is no room to move things.

When I was a kid, I used to enjoy puzzles that consisted of 15 square pieces and one blank space. The idea was to move the pieces around until the pieces were arranged into a particular numeric sequence (or made a picture). It’s immediately obvious that if there is no space, there is no way to move the pieces and whatever order they are in is the order that they will stay in.

It seems that people who want to control everything want exactly that — no space — no void — no possibility for change. It may be related to the mystery of overworking so many people with long hours despite decades of research showing people are more productive with shorter hours.

In a living human being, there is typically “space” in our respiratory system and our digestive system. To have zero space means we cannot eat and we cannot breathe. We do have spaces within our body — ventricles in the brain, sinuses in the head, and — crucially — females have a place that can accommodate the creation of a new life within.

A hive, or a garden, or a city may indeed be crowded, but if it literally has zero space, it dies, just as we would. The void allows flow — in the case of the individual human body, space allows for the flow of food and the flow of air.

A science that has no void, no space, has no flexibility. It is no longer science but dogma.

A budget with no space, no void, means every penny has been pre-assigned and this is not an effective way to budget.

Games typically have space (Go, Chess, Checkers, Monopoly) as do sports (Tennis, Baseball, Soccer, Basketball). Play often consist of using, changing, and manipulating space. The baseball pitcher tries to throw the ball so that it crosses through spaces where the hitter cannot easily hit it well. The hitter tried to hit the ball where the fielders cannot reach the ball. The tennis player tries to “build a point” by creating more space; e.g., by pulling their opponent progressively wider so that a shot can be hit into such a large space that it cannot be reached at all. In most games and sports, the amount of empty space, particularly at the beginning of play is relatively large. In chess, as in American football, play begins with a large space between the teams. In many games, there are special terms for spaces. A “Luft” in chess is a place for your King to go if attacked on the back rank by a queen or rook. In American football, the quarterback throws passes from the “pocket” which is supposed to protect them from tacklers.

To me, “The Void” connotes more than space, however. “The Void” seems to refer to a relatively large, concentrated space. In music, for example, without any space, there is just a long, annoying noise. But “The Void” isn’t just the space between notes. It seems as though it must be a significant silence such as after the tuning and before the first note is played or the space between movements in a symphony.

Of course, we can contemplate things at different scales. If we see Alternating Repetition from a distance that allows us to see the alternating repetition, we might see gaps as spaces, but not as examples of “The Void.” If we moved our point of view so that only one such gap were visible, it might become an example of “The Void” at another scale.

Most of our everyday reality is physically made up of empty space. Every atom is more than 99.999 % empty space. At that scale, it’s mostly void or at least mostly space. And, at the other extreme, although it may seem that space is crowded when you see the Starship Enterprise go through the universe at “Warp 9” that’s an illusion to make it more interesting. Most of the universe (and our solar system) is empty space. The sun which is by far the largest object in our solar system has a diameter of 865,000 miles. That’s big! But the nearest planet, Mercury, is 40 million miles away. And, that planet is the only thing in its orbit.

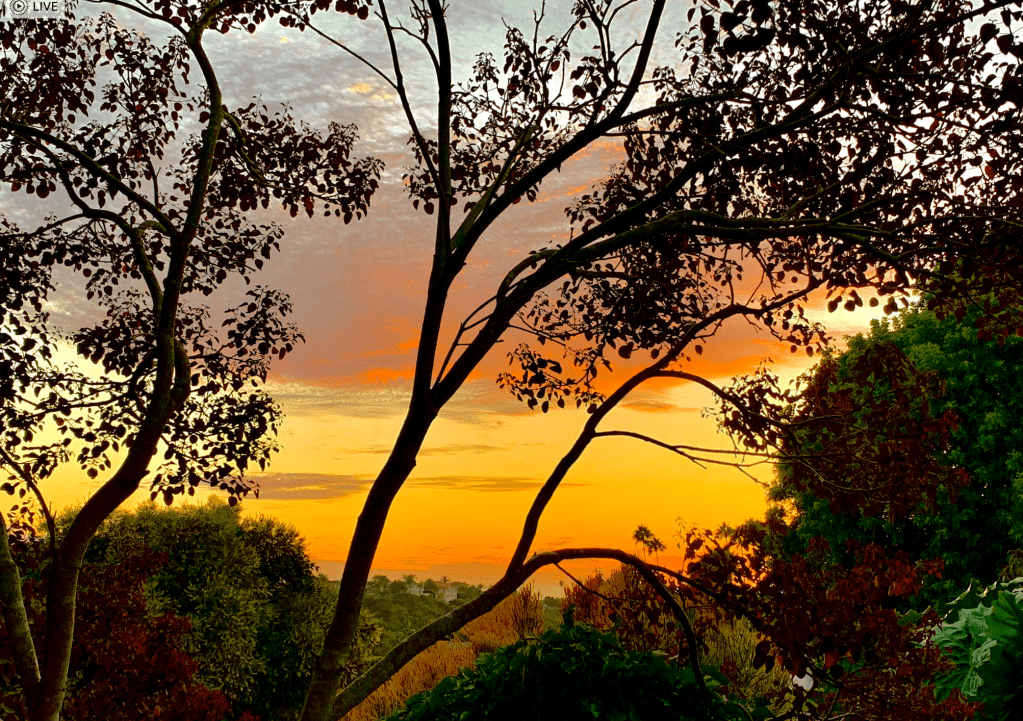

Once I was driving with my family from San Francisco to Salt Lake City. Around 3 am, in the absolute middle of nowhere with no lights and no moon, I stopped the car and ran a quarter mile from the road into the desert to look up at the stars. It doesn’t “look” empty of course. Far from it. Yet the sheer blackness of the background and the vastness of it made it seem like a true void. In fact, because of contrast with the sharp and sparkling stars, the vast void was made into even more of a vast void.

An atrium, a central courtyard, a reflecting pool — can these be voids that strengthen the center?

If we look at a void, does that produce a different aesthetic feeling from when we are in a void that surrounds us? If you and your family or friends or tribe huddle around a campfire at night, the fire is a center. You can see the faces of people in the firelight. But you are aware that each of you knows that surrounding your little group is darkness. Sometimes, in movies, someone will remark, “Well, it’s quiet.” To which, the proper response is, “Yeah. Too quiet!” When the frogs and crickets stop making noise, the heaviness of the silence becomes oppressive. It might mean that large predators are about, each with their own maw of void. Being in a large space that has no perceptible features is awe-inspiring or even fear-inspiring. Looking at a large space that is situated in the context of a pattern may echo that feeling slightly, but to me, it feels very different.

The same tune can be played on a piccolo or a base vile.

When it comes to user experience, what comes to mind for me is the empty page or the empty canvas or the empty spreadsheet. These are large unfilled spaces. To compose, whatever the medium, requires of us a kind of courage. We must “enter” the empty space. In order to write, we must also allow for empty space within us. As I write, I find that there is always a rhythm of “describing” things that have “come up” for explication and then pausing — staring as it were into the blackness, the void, of my own consciousness. I allow things to arise from that inner void and show themselves. I don’t always know what it will be.

I think that process (and not wanting it disrupted) is one reason that I, like so many others, found “Clippy” to be so annoying. Whenever I was allowing for the void to reveal to me what I wanted to say, “Clippy” would imagine I was stuck and offer a suggestion (invariably irrelevant).

Perhaps you or one of your kids has played “8-ball.” You ask it a question then you shake it a little and an answer “appears” in a little window. The most enthralling time is that space between when you ask the question and the answer appears. Of course, it’s fun thinking of the questions and interpreting the answers, but the most dramatic part is waiting for the answer to appear. In that moment, you may suddenly realize what answer you want to appear.

If an application is to support any kind of creative activity, it should not “rush” the user and it should provide the user empty space in which to create. That emptiness can be intimidating, but I still think it’s necessary.

My desktop has many icons, tool bars, and windows. The only true void is the blank part of the writing pane in Pages. Visually, since the blank part of the page is white, it doesn’t seem much like a void. There is enough space between the icons and menu items to make them legible, but there is no “void” there. Visually, the only thing that really strikes me as a void is the totally black rounded rectangle beside the color sphere in the Format window. It’s black because that is the color of the text I’m writing in. Its function is nothing like that of an actual void.

The void may symbolize death, but it also symbolizes life. It is the happening place. It is the dance floor. It is the game board. It is the playing field. It is waiting for the curtain to rise. It is the movie theater when the lights go out but the movie has not begun. It is also the movie theater when the credits have done rolling but before the house lights have come up. If it is death, it is also rebirth. If it is birth, it is also the end.

As every moment of our existence and our attention becomes commoditized and sold to the highest bidder, there is ever more pressure to eliminate the “wasted space” inherent in the void.

Running into the ocean; diving into a pool; deciding to have a child; moving; divorcing; falling in love; losing a loved one; starting a composition; beginning a design — these are moments when we brush up against the void or enter it or avoid it or incorporate it into ourselves. We like to fool ourselves that there is some process or routine or formula or piece of software that can take all the uncertainty out of these transitions into the unknown.

That’s all illusion. It’s the very nature of life itself — that dance on the razor edge between chaos and repetition — to embrace the void. We try always to “avoid” The Void.

Nature doesn’t “abhor a vacuum.” Nature is mostly vacuum.

But we abhor a vacuum. Our productivity tools are geared toward reducing “The Void” as much as possible. Children are shuttled from one high intensity activity to another to ensure that when they apply to college, they will get in one which will ensure that they will get a high-paying job that will enable to them to work their entire lives so that there will be no uncertainty.

I am also a product of that “Avoid The Void” culture, so I find it hard to imagine what it would mean to design a tool or UI or app that embraced and encouraged The Void. There are some specific mobile apps that support meditation or listening to music or breathing. What of composition though? Whether it is programming, writing, drawing, or creating a business plan, is there a place for The Void to be supported? How would you encourage it? What visual elements or other sensory elements could be used to support it? How would you measure how well you did?

Or, is it easier to avoid the whole topic?

—————————————————-